The semester is almost finished, so I finally get a change to upload something to this blog, I’ll begin with the first things we saw on the “Laboratory of electromagnetic devices” class.

For this class session we were asked “How does the electric resistance of a wire depends on its length and cross-sectional area?” and then we were given three nichrome wires of 1 mm diameter each, a rule and a multimeter, then I started to take resistance measurements in steps of 5 cm for one, two and three threaded wires

| 1mm diameter | 2mm diameter | 3mm diameter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

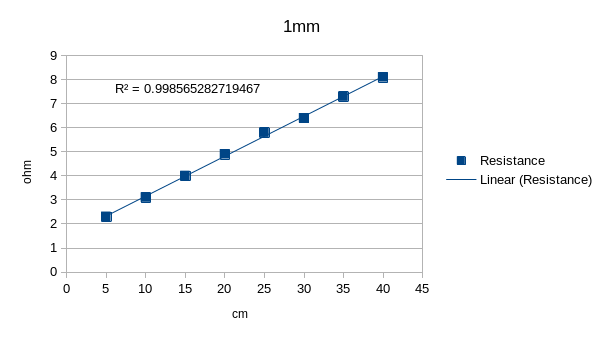

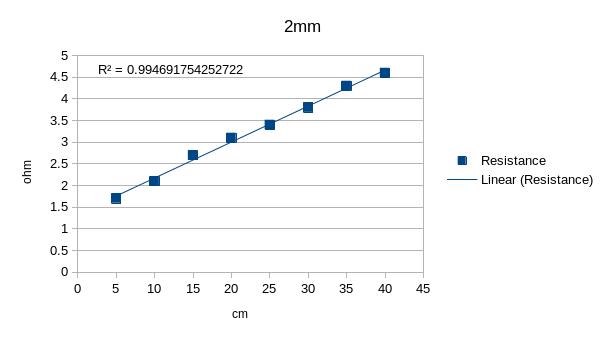

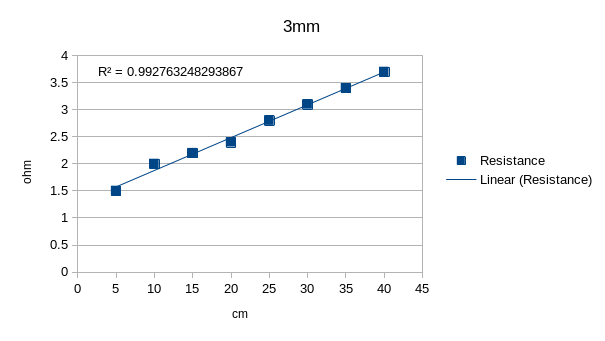

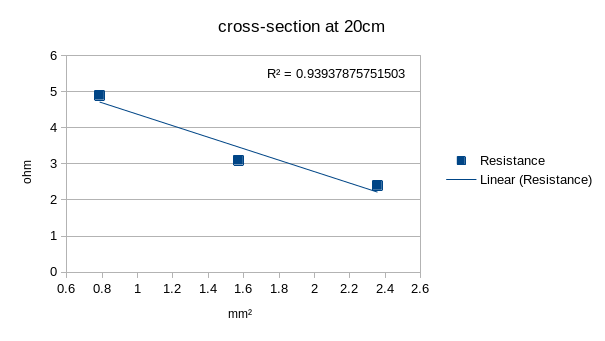

After that I did four scatter plots of the data, three of length vs resistance for each threaded wire and one of cross-sectional area vs resistance at 20 cm of length

| Length vs resistance with one 1mm wire | Length vs resistance with two 1mm wires |

|

|

| Length vs resistance with three 1mm wire | Area vs resistance at 20cm |

|

|

As we can see from the plots, each of them has at least a 92% relation with a linear trend, we can also see that if we take measurements from a greater distance, the resistance goes up, and when we add more wires to the thread the resistance goes down meaning that the resistance of a material is directly proportional to its length and inversely proportional to its cross-sectional area.

Why?

Ok, we got the answer to the question, but why is it that way and not the other way around? To explain this behavior we’ll have to look at Ohm’s law from the physics side.

Everyone knows a little about Ohm’s law but from an electric analysis perspective on a “macroscopic” scale

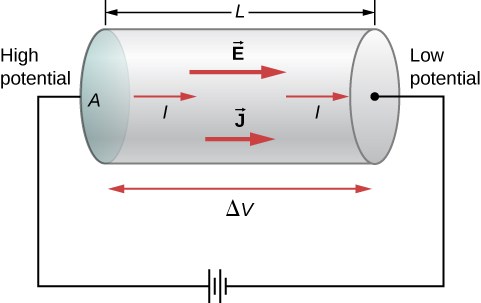

From the physics perspective, we analyze the electric field \(\overrightarrow{E}\) as it is composed of the scalar product of resistivity in ohm/meter \(\rho\) and the current density vector per m² \(\overrightarrow{J}\)

\[\overrightarrow{E}=\rho\overrightarrow{J}\]Then using the definition of voltage between two points of the electric field:

\[\Delta V=-\int_{}^{}\overrightarrow{E}\cdot dl\]Where \(dl\) is the path along the conductor. If the electric field is uniform along the length of the material as it happens with a wire:

Then we can drop the \(\Delta\) and define voltage \(V\) and the magnitude \(E\) as:

\[V=lE \rightarrow E=\frac{V}{l}\]And since the electric field is uniform, so is the current density too, which means we can define the magnitude \(J\) as:

\[J=\frac{I}{a}\]Replacing the values of \(\overrightarrow{E}\) and \(\overrightarrow{J}\) with these new ones we get:

\[\overrightarrow{E}=\rho\overrightarrow{J} \rightarrow \frac{V}{l}=\rho\frac{I}{a}\]Solving for \(V\):

\[\frac{V}{l}=\rho\frac{I}{a} \rightarrow V=\frac{\rho I l}{a}\]If we remove \(I\) from the right side we get

\[\frac{V}{I}=\rho\frac{l}{a}\]And since \(R=\frac{V}{I}\) it means that the resistance of a wire is

\[R=\rho\frac{l}{a}\]Proving that there exists a formula that shows the resistivity is proportional to the length and inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area.